- +352 444 222

- Monday-Friday 12:00-18:00

- 20, avenue Marie-Thérèse, 2132 Luxembourg

Piracy, a corollary of maritime trade, existed as far back as antiquity. In fact, every ancient civilization with a navy practiced it, from the Phoenicians to the Mycenaeans.1)lejournal.cnrs.fr Since ancient times, maritime space has been a place of enrichment, for the benefit of criminals (pirates), state servants (privateers), nations (war fleets) and private players (armaments/companies). Pirates have been around for as long as navigation has existed, and piracy is nothing more or less than brigandage of the seas.

The word pirate comes from the Greek word πειρατης, which in turn comes from the verb πειραω (then from the Latin Pirata) meaning “to strive for”, “to try one’s hand at”, “to try one’s luck at adventure”.2)en.wiktionary.org

By analogy, a hacker is an individual who embezzles funds, acquires goods or data with high added value via the Internet, or copies works without respecting copyright. There are other, more nefarious forms, such as phishing, which involves usurping a corporate identity. Other examples include phishing, ransomware and social engineering.

Cybercriminals are therefore the worthy heirs of a maritime tradition whose navigational space is now the Internet and networks. The cyber and maritime mix has never been so true from an economic point of view.

After looking at the reasons behind maritime cyber crime, defining the economic and strategic stakes involved, and briefly outlining the regulatory framework with its necessary international dimension, we’ll look at the specific features of maritime cyber crime, before looking at the history of cybercriminal attacks linked to the maritime world. We’ll conclude with a look at the lessons learned from these attacks, which have prompted seafaring professionals to reflect and prepare for what is now an obvious fact: hackers (of all kinds, including terrorists) will deploy the tools and strategies they have patiently devised to enrich themselves and compromise the most important economic sector of world trade.

This postulate will form our conclusion, to which we will add a point on the new maritime technological challenge of an existing future that is also a cyber safety issue: the autonomous ship.

First of all, I think it would be useful to clarify the semantic distinction to be made between cyber security and cyber crime.

Without redefining what already exists, we can say that cybersecurity is the protection of computer systems connected to the Internet (and networks), against computer threats to hardware, software and data. The aim of cybersecurity is to limit risks and protect IT assets from malicious attackers. Cybersecurity is the best way to prevent data breaches, identity theft and ransomware hacking.

Cybercrime refers to all criminal offenses (cybercrimes) committed via the Internet or computer networks. Cybercrime therefore takes place in cyberspace. It includes a wide variety of offences:

Key figures:

- France is the world’s 2nd largest maritime area. That’s 643,427 km² of coastline, or 4,668 kms of coastline.1

- 11 million km2 of exclusive economic zone (including overseas territories)

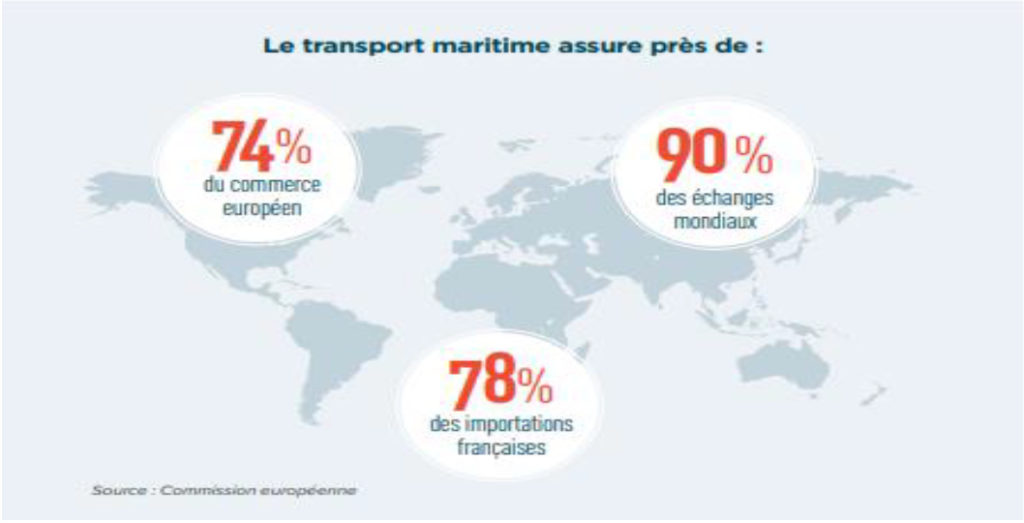

- Maritime economy: €1,500 billion (growing rapidly) – 60,000 merchant ships (1,000 FR units) – 90% of international freight – 334 million tons transported – 50% of communications – 28.3 million passengers in 2017 (Service de la donnée et des études statistiques – Commissariat général au développement durable – 2018)

- Examples of port statistics :

- Mediterranean port traffic: 11 million passengers ;

- Total cruise passengers in 2017: 4.2 million ;

- Container transport: +88% since 2001 ;

- ISPS port areas: Brest – Toulon – Marseille – Le Havre – Port de Bouc – Cherbourg – Calais – St Nazaire

It is therefore clear that the economic stakes involved are such as to arouse covetousness that cyber cannot ignore. Just recently (03/14/2020), the Marseille / Aix en Provence metropolitan area was the target of a cyber ransomware attack of unprecedented scale. Collateral damage from this attack was suffered by a subsidiary of a major French maritime group, whose PCs were encrypted. An investigation is underway.

The link is ideal for presenting a criminal law system that has had to reinvent itself over the years in the face of fast-changing technology. As a result, cybercrime has many faces.

First of all, the stakes are so high that preserving these maritime economic tools has become a priority for legislators and IT security players in our country. In the port areas mentioned above, major French shipping companies have been defined as OIVs (article R. 1332-1 of the French Defense Code – Military Programming Act 2014-2019) or OSEs (proposed by ANSSI and validated by the French Prime Minister). The NIS directive3)NIS Directive coordinating security actions at European level.

In terms of criminal law enforcement, the fight has been organized over the past 10 years. Without making an inventory “à la Prévert”, I retain these major texts 4)Important legislation:

The nature of security risks and APTs (advanced persistent threats) is constantly evolving, making it a real headache to ensure cybersecurity, both on land and at sea.

Cybersecurity threats can take many forms:

Unfortunately, we can illustrate cybercrime in the maritime world without looking too far. Remember:

June 25, 2015: SABELLA sinks the first productive tidal turbine 2kms off Ouessant. In October, a virus attack on the SABELLA turbine’s communication servers, neutralizing the connection with the control center for two weeks. The attack was accompanied by a ransom demand.

June 2017: MAERSK was one of the first large-scale maritime victims of the Petya Not Petya (wannacry) epidemic. 300 million in losses. “Imagine a company where a ship with 10 to 20,000 containers enters a port every 15 minutes, and for 10 days you have no IT” (MAERKS CEO). Note: In France, AUCHAN, SNCF and SAINT GOBAIN were affected.

September 2018: the ports of Barcelona and San Diego targeted. The first to be hit was the port of Barcelona, Spain, on September 20. The second attack was reported on September 25 from the port of San Diego, USA. The aim was to neutralize commercial transactions between companies and their ships. Goal not reached. The second objective was to slow down land-based operations such as ship unloading and loading. Goal achieved.

A final edifying example of maritime cybersecurity is provided by the Israeli cyberdefense solution provider NAVAL DOME, which conducted an experiment on a 260 m container ship. After infecting the ship’s captain’s computer via e-mail, a team from NAVAL DOME compromised the navigation system, radars and engine room management system. This enabled them to divert the ship from its original course and disable the engines. An absolute hazard on the shipping lanes.

As the world’s second-largest maritime empire, France reacted by publishing a report from the Secrétariat Général de la Mer (Matignon) in November 2018, which pledged to take the measure of the challenges associated with cybersecurity in the maritime domain. A year later, a project supported by the Brittany region, highlights the willingness of many maritime cybersecurity players to make a real commitment. For example, the idea of creating a CERT5)Computer Emergency Response Team- Maritime in Brest (initiative supported by GYCAN6)Groupement des Industries de Construction et Activités Navales (French shipbuilding industry association)) is now a proven probability. As ANSSI is the only CERT in France, this would provide a complementary maritime response to all the French maritime players who are calling for its creation.

We should also mention that the French Navy has responded to the various maritime threats by setting up a MICA Center8 at the Préfecture Maritime in Brest three years ago. Today, the MICA Center is a major player in the detection of organized maritime crime (cyber or otherwise).

Last but not least, I must mention the only judicial investigation service dedicated to the world of the sea, the national unit for combating maritime cybercrime, CYBERGENDMAR. Part of the Maritime Gendarmerie’s Research Section, with nationwide jurisdiction, this unit carries out cyber-related judicial investigations involving all maritime players, both on land and on board the ships on which it may be deployed.

After this long presentation of a subject that has fascinated me for years through the investigations I’ve carried out and the encounters I’ve had, I hope I’ve been able to enlighten you on a little-known form of cybercrime.

Awareness of the threat of maritime cybercrime is such that ENSM9, the Cyber Navale Chair, in collaboration with IMT Atlantique, ENSTA Bretagne and the École navale, have joined forces to offer a Specialized Master’s degree in “cybersecurity of maritime and port systems” (starting in September 2020).

Technological innovation in the marine sector is a constant. In order to reduce the risks associated with navigation, as well as those inherent in economic activity, today already but even more so tomorrow, we will see the advent of the era of autonomous ships on the world’s seas. This is no longer a utopian dream, since autonomous ships are already in operation for simple transport operations. Tomorrow, crossing an ocean will be a reality.10

This means being able to anticipate cyber-attacks against these autonomous ships. It’s a tall order, but I have no doubts about our ability to rise to it. The tools exist and the will is already being coordinated, as I have already explained.

I’d like to conclude with the words of Seneca, which remain as much a maritime truth today as they ever were: ” When you don’t know which port you’re sailing towards, no wind is the right one”.

[+]

| ↑1 | lejournal.cnrs.fr |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | en.wiktionary.org |

| ↑3 | NIS Directive |

| ↑4 | Important legislation |

| ↑5 | Computer Emergency Response Team |

| ↑6 | Groupement des Industries de Construction et Activités Navales (French shipbuilding industry association) |

Dear users, on 15/06/2022 Internet Explorer will be retiring. To avoid any malfunctioning, we invite you to install another browser, such as Google Chrome, by clicking here, or the one of your choice.

Please check this before contacting us in the event of a problem.